COPD Risk Calculator

Your COPD Risk Assessment

Enter your information to see your risk level

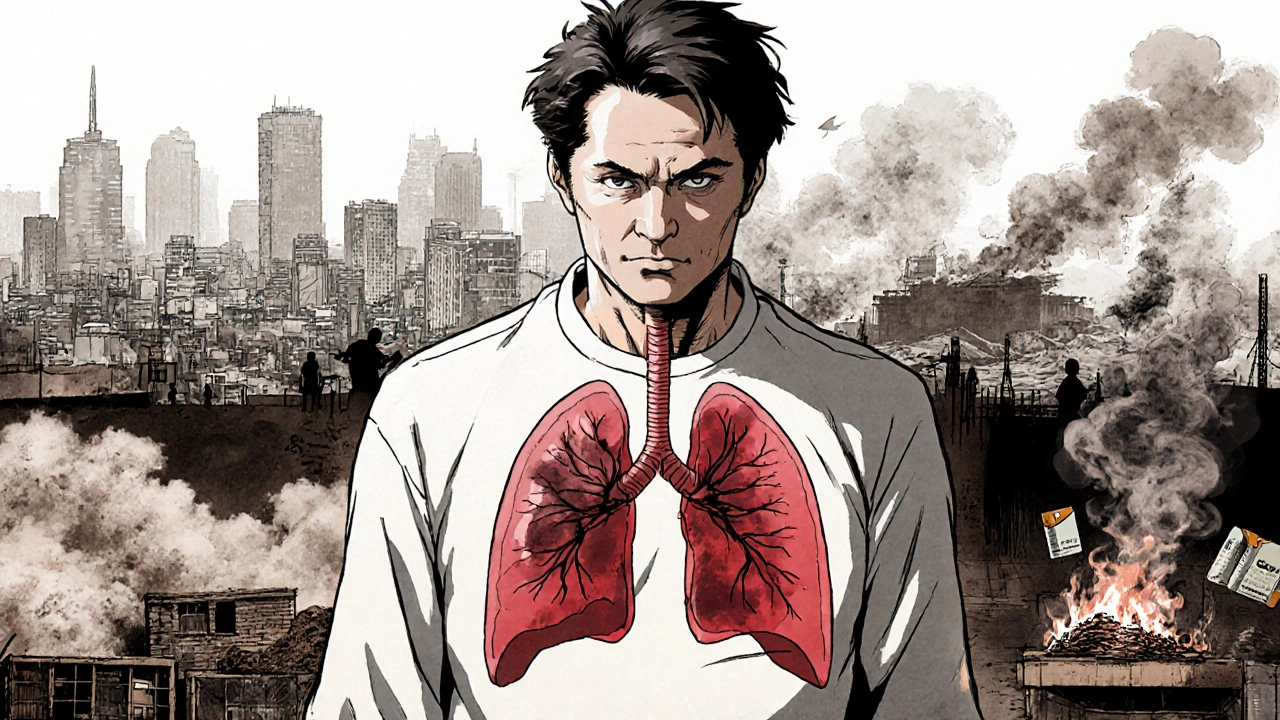

When you hear the term Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease is a progressive lung disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation, you might picture an older smoker struggling for breath. While smoking is the headline culprit, the web of causes stretches far beyond cigarettes. This guide unpacks the major drivers, how they interact, and what you can do to lower your odds.

Key Takeaways

- Smoking accounts for about 85% of COPD cases worldwide.

- Long‑term exposure to outdoor air pollution, occupational dust, and indoor biomass fuels adds 10‑20% to the risk.

- Genetic predisposition, especially Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency, can trigger COPD even in never‑smokers.

- Age, gender, and low socioeconomic status magnify every other risk.

- Early detection via Spirometry can halt progression before severe damage occurs.

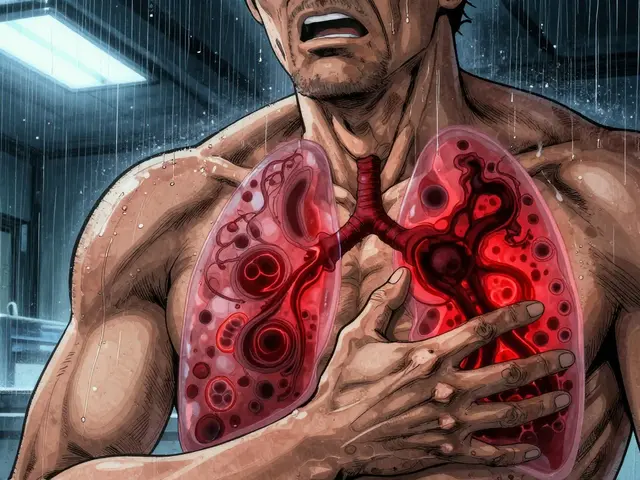

What Exactly Is COPD?

COPD combines two main pathologies: Chronic Bronchitis, an inflammatory narrowing of the airways, and Emphysema, the destruction of alveolar walls. Most patients have a mix of both, which explains the wide range of symptoms-from a persistent cough to breathlessness on a short walk.

The disease is measured by the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) relative to the total lung capacity. A post‑bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.70 confirms the diagnosis.

Smoking: The Dominant Destroyer

Tobacco Smoking remains the single biggest risk factor. Each pack‑year (one pack per day for one year) raises the odds of COPD by roughly 1.5‑2 times. The toxic cocktail of nicotine, tar, and over 7,000 chemicals irritates the airway lining, accelerates mucus production, and triggers an inflammatory cascade that ultimately damages the capillary network.

Even former smokers retain a higher baseline risk for up to 10 years after quitting, although the slope of lung‑function decline flattens dramatically after cessation. That’s why primary‑care providers stress quitting as the most effective single intervention.

Air Pollution - The Invisible Threat

Outdoor pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), and ozone (O₃) act as silent aggressors. Long‑term exposure (10+ years) to PM2.5 concentrations above 35 µg/m³ correlates with a 12% increase in COPD incidence, independent of smoking status.

Urban dwellers in developing megacities often face double exposure-high traffic emissions plus indoor cooking smoke-creating a cumulative burden that accelerates lung‑function loss by an estimated 30 mL per year.

Occupational Hazards

Jobs that involve dust, fumes, or chemicals leave a fingerprint on the lungs. Workers in mining, construction, agriculture, and manufacturing are exposed to silica, coal dust, and metal fumes. A landmark cohort study from the European Respiratory Journal found that miners with ≥20 years of exposure had a 1.8‑fold higher COPD risk, even after adjusting for smoking.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) and regular respiratory health screenings are the only proven mitigations for this group.

Biomass Fuel & Indoor Air Quality

In many low‑income households, cooking on open fires or poorly ventilated stoves uses wood, charcoal, or dung. The resulting smoke contains high levels of carbon monoxide and particulate matter. WHO estimates that over 3 billion people are exposed daily, contributing to roughly 5% of global COPD cases.

Switching to cleaner fuels or installing chimneys can cut indoor particulate exposure by up to 70%, translating into measurable improvements in FEV1 over a 5‑year period.

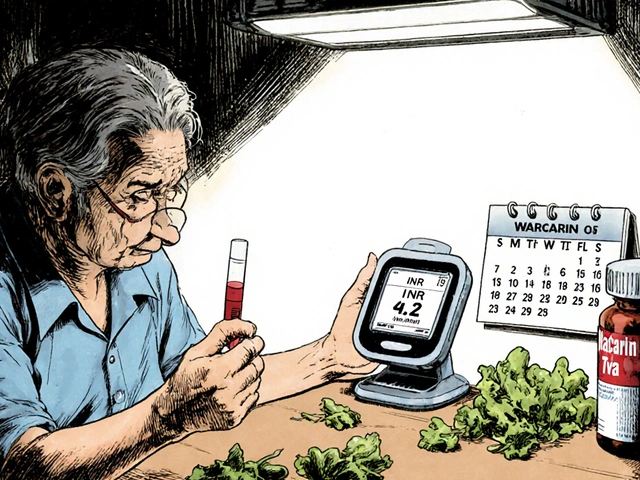

Genetic Predisposition - Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin Deficiency

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (A1ATD) is the only known hereditary cause of COPD. Individuals with the ZZ genotype have a 10‑15% chance of developing emphysema before age 45, even if they never smoked.

Screening first‑degree relatives of diagnosed patients is recommended, because early augmentation therapy can slow disease progression.

Other Amplifiers: Age, Gender, and Socio‑Economic Status

Age is a non‑modifiable risk-lung elasticity naturally declines after 40, and the cumulative burden of exposures becomes evident. Women appear more susceptible to smoke‑induced COPD; hormonal differences may affect airway inflammation, leading to a 1.3‑fold higher risk compared to men with similar smoking histories.

Low socioeconomic status compounds risk through higher smoking rates, poorer housing conditions, and limited access to preventive care. A 2023 US study linked Medicaid enrollment with a 22% increase in COPD hospitalizations.

Comparing the Major Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Typical Exposure Metric | Relative Risk Increase | Population Impact (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco Smoking | Pack‑years | 1.5‑2.0× per pack‑year | ≈85% |

| Air Pollution (PM2.5) | µg/m³ (annual avg.) | 1.12× per 10 µg/m³ | ≈10‑15% |

| Occupational Dust/Fumes | Years in high‑exposure job | 1.8× for >20 years | ≈5‑7% |

| Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin Deficiency | Genotype (ZZ) | 10‑15% absolute risk | ≈0.5% |

| Biomass Fuel Smoke | Hours of indoor cooking per day | 1.3‑1.5× | ≈5% |

Putting It All Together - The Cumulative Model

The risk of COPD isn’t a simple checkbox; it’s a layered stack. Think of each factor as adding a brick to a wall of damage. A lifelong non‑smoker exposed to high indoor smoke may still develop COPD if they also have A1ATD and work in a dusty environment. Conversely, a smoker who quits early, lives in a low‑pollution area, and has no genetic predisposition may never cross the disease threshold.

Clinicians often use a “risk score” that weights each brick. The most widely adopted is the COPD Prediction Model (COPD‑PM), which incorporates age, smoking pack‑years, BMI, and exposure to occupational dust. Adding genetic testing for A1AT improves predictive accuracy by 6%.

How to Reduce Your Personal Risk

- Quit smoking. Seek nicotine‑replacement therapy, counseling, or prescription medications. Within a year, lung‑function decline slows to near‑baseline.

- Minimize outdoor exposure on high‑pollution days. Use air‑purifying filters indoors and check local AQI apps.

- If you work with dust or fumes, wear approved respirators and undergo regular spirometry checks.

- Switch to clean cooking fuels or improve ventilation with chimneys and exhaust fans.

- Consider genetic screening if you have a family history of early‑onset emphysema.

- Stay physically active. Aerobic exercise improves airway clearance and overall lung capacity.

Early detection matters. If you have chronic cough, sputum production, or shortness of breath, ask your doctor for a Spirometry test. Catching COPD in Stage I or II can keep you out of the hospital for years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can non‑smokers really get COPD?

Yes. About 15‑20% of COPD patients worldwide have never smoked. Their disease is usually linked to long‑term air‑pollution exposure, occupational dust, indoor biomass smoke, or genetic factors like Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin Deficiency.

How long does it take for smoking cessation to improve lung function?

Lung‑function decline slows markedly within the first 6‑12 months after quitting. Full reversal of airway inflammation may take several years, but the risk of severe COPD drops by 50% after a decade of abstinence.

Is there a screening test for COPD risk?

Spirometry is the gold‑standard diagnostic tool. For high‑risk groups (heavy smokers, occupational exposure, age > 40), annual spirometry is recommended even if symptoms are absent.

What role does genetics play aside from Alpha‑1 Antitrypsin?

Beyond A1AT, genome‑wide association studies have identified variants in genes like HHIP, GSTP1, and CHRNA5 that modestly increase COPD susceptibility. However, environmental triggers still dominate the risk profile.

Can exercise prevent COPD?

Regular aerobic activity (e.g., brisk walking, cycling) strengthens respiratory muscles, improves mucus clearance, and can offset some of the functional loss caused by exposure. While it won’t replace quitting smoking, it’s an essential part of a risk‑reduction plan.

Understanding the web of causes empowers you to act before irreversible damage sets in. Whether you’re a smoker ready to quit, a worker exposed to dust, or someone who cooks on an open fire, targeting these risk factors can keep your lungs breathing easy for years to come.

Sajeev Menon

October 22, 2025 AT 16:52Great rundown of the COPD drivers, and I especially like how you highlighted the role of indoor biomass smoke. Many people in rural areas overlook that their kitchen stove can be just as harmful as a pack of cigarettes. The data on occupational dust exposure is eye‑opening, particularly for miners and construction workers. Remember to check ventilation when using any open flame at home – it's a simple step that can save lungs later.

Joe Waldron

October 26, 2025 AT 17:05Reading this makes me think of how interconnected the risk factors really are,; smoking clearly tops the list, but you can't ignore the cumulative impact of air pollution, occupational hazards, and genetics,; each adds a layer of vulnerability,; and the socioeconomic angle ties it all together,; which is why public health policies need to be multifaceted,; not just anti‑smoking campaigns.

Wade Grindle

October 30, 2025 AT 18:18Solid summary, and the table gives a quick visual of the relative contributions. It's worth noting that the 10‑15% figure for alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency is a global estimate; local prevalence can vary quite a bit. Also, the risk from PM2.5 really spikes in megacities where traffic and industry overlap.

Benedict Posadas

November 3, 2025 AT 05:38Totally agree with @Joe – the stack of risk factors feels like building a wall of damage. 😅 If you can knock down even one brick, like quitting smoking, the whole structure gets weaker. Also, watch out for typos in those big tables – a misplaced decimal can change the story! 😂

Jai Reed

November 7, 2025 AT 20:45One of the most important take‑aways from this guide is that COPD risk is not a binary switch but a cumulative score that can be quantified. The COPD Prediction Model (COPD‑PM) integrates age, smoking pack‑years, body mass index, and occupational exposure into a single risk number. Adding alpha‑1 antitrypsin genotype data improves this predictive accuracy by about six percent, which can be the difference between early detection and missed diagnosis. Studies have shown that each additional decade of exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) raises the odds of developing COPD by roughly twelve percent, independent of smoking status. In practical terms, this means that someone who lives in a high‑pollution city for 30 years accumulates a risk comparable to a moderate smoker. Occupational dust exposure follows a similar additive pattern; a miner with twenty years of silica exposure faces nearly double the risk, even if they have never lit up a cigarette. The socioeconomic factor acts as an amplifier, because limited access to preventive care often leads to delayed spirometry testing, which in turn allows the disease to progress unchecked. Gender differences also matter: women tend to develop COPD at lower pack‑year thresholds, likely due to hormonal influences on airway inflammation. While genetics beyond alpha‑1 antitrypsin play a modest role, variants in genes such as HHIP and GSTP1 have been linked to increased susceptibility, especially when combined with environmental triggers. Importantly, the model emphasizes that interventions are most effective when applied early; quitting smoking can halve the projected decline in FEV1 within five years. Likewise, installing proper ventilation in homes that rely on biomass fuels can reduce indoor particulate concentrations by up to seventy percent, translating into measurable improvements in lung function over a five‑year horizon. Regular aerobic exercise, such as brisk walking or cycling, strengthens respiratory muscles and promotes better mucus clearance, offering another layer of protection. Finally, annual spirometry for high‑risk groups-people over 40 with a smoking history, exposure to dust, or a family history of early‑onset emphysema-remains the gold standard for early detection, allowing clinicians to intervene before irreversible damage sets in.

Sameer Khan

November 11, 2025 AT 08:05The pathophysiological interplay between chronic bronchitis and emphysema can be framed through the lens of protease‑antiprotease imbalance, oxidative stress, and impaired mucociliary clearance. In alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency, the deficiency of serpin A1 leads to unopposed neutrophil elastase activity, accelerating alveolar wall destruction. Moreover, particulate matter induces cytokine cascades-IL‑6, TNF‑α-that potentiate airway remodeling. From a systems‑biology perspective, the cumulative exposure model aligns with dose‑response relationships observed in epidemiologic cohorts, reinforcing the need for multivariate risk assessment tools.

WILLIS jotrin

November 14, 2025 AT 05:32I appreciate the depth of the long comment, especially the emphasis on early spirometry and lifestyle modifications. It reminds us that while genetic predisposition is immutable, environmental factors remain modifiable, and that's where public health can make a real impact.

Kiara Gerardino

November 16, 2025 AT 13:05Only those who refuse to confront the plain data should dare ignore the glaring link between pollution and COPD!

Joanne Ponnappa

November 18, 2025 AT 06:45True, the evidence is undeniable. 🌍 Let’s keep pushing for cleaner air policies and better workplace protections.

Michael Vandiver

November 19, 2025 AT 10:32Great info, thanks!

Tim Blümel

November 21, 2025 AT 18:05This guide nails the practical steps we need to take. 🌱 Quitting smoking is the cornerstone, but adding clean‑fuel stoves and regular exercise rounds out the strategy. I’d add that community health programs should offer free spirometry screenings in high‑risk neighborhoods. Also, workers in dusty jobs deserve mandatory respirators and periodic lung‑function checks. Keep sharing these insights-knowledge is the best prevention.