Beers Criteria Medication Checker

Check Medication Safety for Older Adults

This tool helps identify medications that may be inappropriate for older adults according to the Beers Criteria guidelines. Enter medications below to see if they're flagged as potentially harmful.

Every year, over 1.3 million older adults in the U.S. are hospitalized because of medication problems. Most of these cases aren’t accidents-they’re preventable. When someone turns 65, their body changes. Kidneys slow down. Liver metabolism drops. Brain receptors become more sensitive. But prescriptions don’t always adjust. A 72-year-old might be on seven different pills, some of which were written years ago and never reviewed. One of them could be doing more harm than good.

Why Older Adults Are at Higher Risk

The risk isn’t just about taking more pills. It’s about what those pills do to an aging body. By age 70, kidney function drops by nearly 50% compared to when someone was 30. That means drugs like ibuprofen or certain antibiotics stay in the system longer. They build up. And that’s when trouble starts.Take NSAIDs like indomethacin or ketorolac. They’re common for arthritis pain. But in older adults, they raise the risk of stomach bleeding and kidney failure. A 2025 JAMA Network Open review found that older adults prescribed these drugs were 26% more likely to have an adverse drug event-especially if they were also on blood thinners or diuretics.

Then there’s the brain. Benzodiazepines like lorazepam or alprazolam, often prescribed for anxiety or sleep, can cause confusion, falls, and even dementia-like symptoms. One study showed that seniors on these drugs were 60% more likely to experience functional decline within six months. And it’s not just one drug. When multiple high-risk medications are layered together-say, an anticholinergic for overactive bladder, a benzodiazepine for sleep, and an opioid for pain-the risk multiplies.

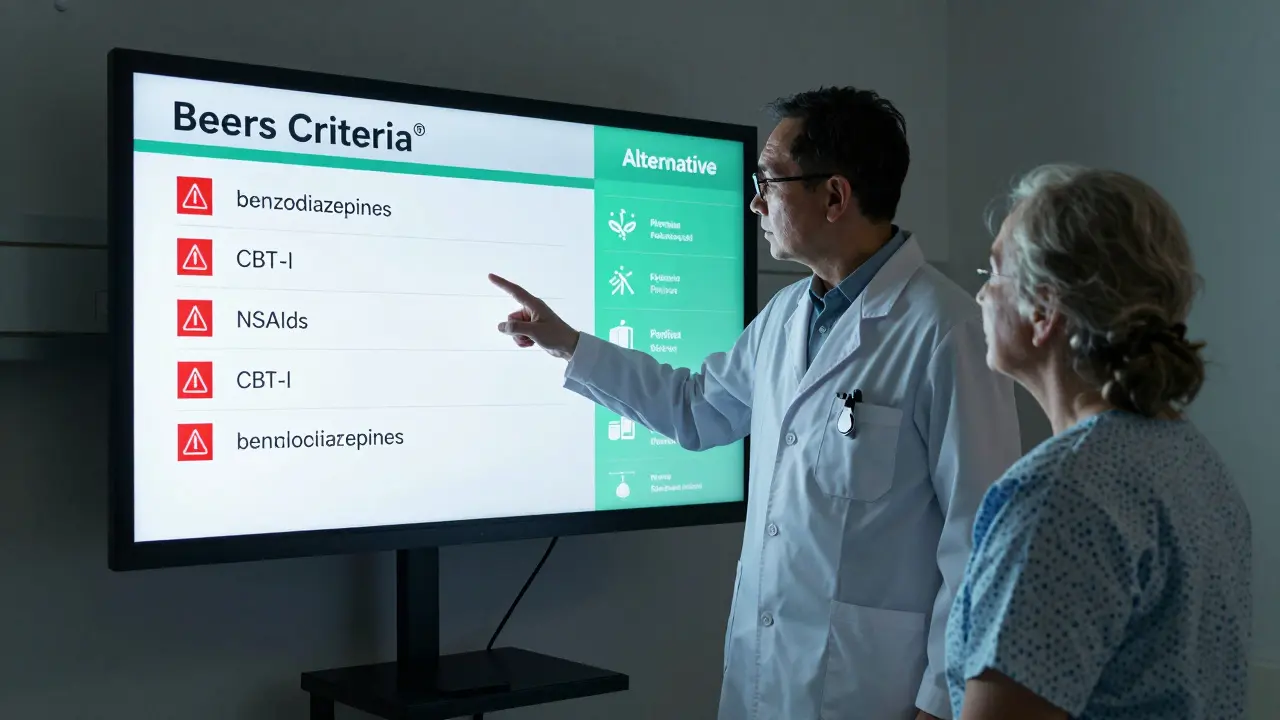

The Beers Criteria: The Gold Standard for Safer Prescribing

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria® is the most trusted guide for spotting dangerous medications in older adults. First published in 1991, it’s been updated every three years. The 2023 version lists 139 medications or drug classes that should be avoided-or used with extreme caution-in people 65 and older.It’s not just a list. It’s a system. Some drugs are outright inappropriate for nearly all older adults. Others are risky only under certain conditions-like if the person has kidney disease, low blood pressure, or is already on another drug that interacts badly.

For example, tramadol, once seen as a safer opioid, is now flagged because it can trigger hyponatremia-a dangerous drop in sodium levels-especially when taken with SSRIs or diuretics. Aspirin, once routinely recommended for heart disease prevention in older adults, is now cautioned against for anyone 70 or older unless they’ve already had a heart attack or stroke. Why? Because the bleeding risk outweighs the benefit for most people in that age group.

What makes the Beers Criteria powerful is how widely it’s used. Epic’s electronic health record system now includes Beers Alerts in 87% of its geriatric-focused installations. That means when a doctor tries to prescribe a flagged drug to a 75-year-old, the system pops up a warning. But here’s the catch: 65% of those alerts get overridden. Why? Because many are too broad. Warfarin for atrial fibrillation? Beers says it’s okay. But the system doesn’t always know that.

The Missing Piece: What to Use Instead

Knowing what not to prescribe is only half the battle. The bigger problem? Doctors often don’t know what to prescribe instead.In a 2023 survey of 1,200 primary care doctors, 68% said they struggled to find safe, effective alternatives when trying to stop a harmful medication. That’s why the American Geriatrics Society released the AGS Beers Criteria® Alternatives List in July 2025.

This isn’t just another drug list. It’s a toolkit. It gives 47 evidence-backed alternatives-half of them non-drug options. For insomnia? Instead of benzodiazepines, try cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which has been shown to work better and last longer. For overactive bladder? Pelvic floor exercises and timed voiding can reduce symptoms without anticholinergics. For chronic pain? Physical therapy, heat therapy, or low-dose acetaminophen (with liver monitoring) are safer than opioids or NSAIDs.

These aren’t theoretical suggestions. They’re real, tested approaches used in clinics across the country. At Mayo Clinic’s emergency department, pharmacists started using these alternatives during discharge planning. Within six months, they cut PIMs by 38%.

How Hospitals Are Fixing This-And Where They’re Failing

Some hospitals are making real progress. The University of Alabama at Birmingham’s ED reduced 30-day readmissions from medication errors by 22% by adding a clinical pharmacist to every geriatric patient’s discharge plan. They reviewed every medication, asked patients what they were actually taking, and replaced risky drugs with safer ones.But it’s not easy. Implementing these changes takes time, training, and staffing. The Geriatric Emergency Medicine Guidelines recommend at least 8 hours of training for staff and a full-time equivalent pharmacist for every 20,000 annual ED visits. Only 31% of rural EDs have that level of support.

And alert fatigue is real. One ER doctor in Texas told Medscape: “I get 12 Beers warnings per shift. Half of them are for drugs that are totally appropriate. I stop reading them.” That’s why CMS is updating its Measure 238 for 2026. Instead of just tracking high-risk prescriptions, it will now track whether doctors actually deprescribe them. It’s a shift from punishment to progress.

What Patients and Families Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. If you or a loved one is over 65 and on five or more medications, ask these questions:- Is this drug still needed? Could it have been stopped years ago?

- Are there non-drug options we could try first?

- Could this interact with another medicine I’m taking?

- Has my kidney function been checked recently?

- Who is responsible for reviewing all my meds together?

Bring a list of every pill, supplement, and over-the-counter drug to every appointment-even the ones you think are harmless. Many seniors take melatonin, St. John’s wort, or calcium supplements without realizing they can interfere with heart meds or blood thinners.

And if your doctor says, “We’ve always done it this way,” push back. Evidence changes. So should prescriptions.

The Future Is Integrated

The next big step? Connecting care. Right now, a senior might get a safe discharge plan from the ER, only to return to a primary care doctor who doesn’t know what was changed. Or a pharmacist might deprescribe a drug, but the specialist keeps prescribing it.The Johns Hopkins A. Hartford Foundation’s 2025 roadmap calls for seamless medication management-from the emergency room to the home. That means shared records, coordinated care teams, and regular med reviews every three months, not just once a year.

By 2030, medication-related problems could cost the U.S. healthcare system over $500 billion. But we already have the tools to stop it: better guidelines, better alternatives, better training, and better communication. The question isn’t whether we can fix this. It’s whether we’ll choose to.

Roshan Joy

January 11, 2026 AT 21:20Really solid breakdown. I work with elderly patients in Delhi and see this daily. One grandma was on 9 meds - turned out 4 were pointless after her stroke. CBT-I for sleep? Game changer. No more lorazepam, better sleep, no falls. 🙌

Michael Patterson

January 12, 2026 AT 17:18Look i know this is all well and good but like… who the hell has time to review 7 meds every 3 months? My uncle’s doc barely looks at his scrip before hitting print. And dont get me started on the EHR alerts - theyre like a broken fire alarm. 12 warnings a shift? i just click ‘ignore’ and move on. its not that i dont care, its that the system is designed to make me feel like a monster for doing my job. also… why is everyone suddenly an expert on kidney function? i thought we were talking about meds not biochemistry class. 🤷♂️

Priscilla Kraft

January 13, 2026 AT 08:32As a geriatric nurse, I can confirm: the Beers Criteria saved my unit. We started using the Alternatives List last year - pelvic floor exercises for incontinence, melatonin instead of benzos, even walking groups for chronic pain. Our fall rate dropped 41%. But the real win? Families finally feel like they’re part of the plan. Bring a list. Ask the questions. You’re not being difficult - you’re saving lives. 💙

Sean Feng

January 13, 2026 AT 16:39Vincent Clarizio

January 15, 2026 AT 02:49Man this is deep. In Nigeria we dont even have enough pills for the old folks. Some take half doses just to make it last. But when they do get meds? Same problems. One uncle was on ibuprofen every day for back pain - ended up in the hospital with a bleed. No one told him. No one checked his kidneys. We need this list here too. Thank you for writing this.

Alex Smith

January 16, 2026 AT 17:41Let’s be real - this whole ‘Beers Criteria’ thing is just glorified gatekeeping. Doctors are trained to fix things, not take them away. And now we’re supposed to replace opioids with… yoga? CBT-I? Please. If a 78-year-old needs a pill to sleep, let them have it. You think they’re choosing dementia over a good night’s rest? The real issue is we’ve turned medicine into a moral crusade. And the elderly? They’re just collateral damage in the war against ‘inappropriate prescribing.’

Priya Patel

January 17, 2026 AT 03:08My Nana’s on 6 meds. I made a color-coded chart with pics so she knows what to take when. She laughs at it but now she actually takes the right ones. Also, we ditched the melatonin - turns out it messed with her blood thinner. Who knew? 🤫 I’m just a granddaughter with too much time on her hands but… maybe we all should be doing this?

Matthew Miller

January 17, 2026 AT 08:21Oh wow. Another feel-good article from the ‘we’re-all-just-trying-to-save-grandma’ cult. Let me guess - the author has never had to manage a 72-year-old with dementia, COPD, and atrial fibrillation on 11 drugs while their family screams for ‘something stronger.’ You think CBT-I fixes pain from metastatic bone cancer? You think pelvic floor exercises stop the shaking? This isn’t prevention - it’s ideological purity disguised as medicine. The system is broken, but your solution is just more paperwork for people who are already drowning.

Sam Davies

January 19, 2026 AT 06:04Ah yes, the Beers Criteria - the medical equivalent of a Pinterest board for geriatric wellness. So charming. The fact that 65% of alerts are overridden speaks volumes - not about doctors being reckless, but about how poorly these guidelines are implemented. It’s like giving someone a map to Paris… but the map is in Braille and they’re blind. Also, ‘non-drug options’? How quaint. Next you’ll tell me to hug the arthritis away.

Madhav Malhotra

January 20, 2026 AT 01:55Love this! In India, we have this thing called ‘dadi ki dawa’ - grandma’s home remedy. Sometimes it’s turmeric, sometimes it’s prayer. But when it comes to real meds? We need clarity. My aunt was on an anticholinergic for 8 years - no one told her it was linked to memory loss. Now she’s on timed voiding and a water bottle schedule. She’s happier. And she still gets her chai. 🫖

Jennifer Littler

January 21, 2026 AT 21:00As a clinical pharmacist, I can say the Alternatives List is the most underutilized tool in geriatrics. But here’s the kicker - 83% of primary care docs don’t know it exists. We’re not talking about obscure journals. It’s published by the AGS, linked in Epic, and backed by RCTs. Yet, we’re still prescribing tramadol + SSRIs like it’s 2012. The problem isn’t awareness - it’s inertia. And inertia kills.

Jason Shriner

January 22, 2026 AT 12:51so like… what if the old person just wants to feel okay? not ‘optimal’ not ‘evidence-based’ just… okay? you take away their benzo and give them ‘guided breathing’? cool. now they’re wide awake at 3am wondering why their body is betraying them. sometimes the pill is the only thing keeping them from crying. and you wanna take that away with a powerpoint?

Alfred Schmidt

January 22, 2026 AT 15:53THIS. IS. A. CRISIS. I’ve seen it. My mom was on ketorolac for 18 months - kidney failure. They didn’t check her labs. The doctor said, ‘She’s fine.’ FINE? She was peeing blood. And now? She’s on dialysis. And the system? Still pushing NSAIDs like they’re candy. Someone needs to sue. Someone needs to burn the EHR system down. Someone needs to stop pretending this is ‘medicine’ and start calling it what it is - negligence with a stethoscope.

Christian Basel

January 23, 2026 AT 14:39Pharmacokinetic changes in geriatric populations are non-linear and heavily modulated by polypharmacy-induced cytochrome P450 inhibition, particularly CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 isoforms. The Beers Criteria, while clinically pragmatic, lacks granularity in pharmacodynamic profiling - especially regarding receptor sensitization thresholds in aging CNS tissue. Furthermore, the proposed alternatives lack adequate pharmacoeconomic validation in Medicaid populations, rendering them impractical in resource-constrained settings. The 2025 Alternatives List is a well-intentioned heuristic that fails to account for heterogeneity in frailty indices.

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 25, 2026 AT 10:32My dad is 76. He takes 5 pills. I asked the doctor: ‘Can we cut one?’ He said yes - the aspirin. No heart attack. No stroke. Just bleeding risk. We stopped it. He’s fine. No drama. No magic. Just common sense. Maybe we don’t need new lists. Maybe we just need to ask.