Every time someone takes a pill, there’s a balance being struck-between what the medicine can do and what it might harm. It’s not just about whether a drug works in a lab or in a clinical trial. It’s about whether it’s safe when taken by millions of different people, with different bodies, different habits, and different health problems. That’s where the science of medication safety comes in. It’s not guesswork. It’s not luck. It’s a rigorous, data-driven field built to answer one question: When does the benefit of a drug outweigh its risks?

Why Clinical Trials Aren’t Enough

Clinical trials are the starting point, not the finish line. A new drug might be tested on 2,000 people over two years before it hits the market. That sounds like a lot-until you realize that rare side effects can show up in just 1 out of every 10,000 people. Those events? They’re invisible in trials. A heart rhythm problem. A sudden liver failure. An allergic reaction that only shows up after six months of use. These don’t show up in controlled studies because there just aren’t enough people, or enough time.

That’s why, after approval, drugs don’t disappear into pharmacies and vanish from scrutiny. They enter a new phase: real-world monitoring. Think of it like a national early-warning system. Every prescription filled, every hospital admission, every emergency room visit linked to a medication-those are data points. And they’re collected on a scale trials never could. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative tracks over 190 million people. Kaiser Permanente’s system covers 12.5 million. Medicare data includes 57 million beneficiaries. These aren’t just numbers. They’re real lives.

How Scientists Track Hidden Dangers

Researchers don’t just look at what happens after a drug is taken. They look for patterns. One powerful method is the self-controlled case series (SCCS). Instead of comparing one person to another, it compares the same person to themselves-before and after taking the drug. If someone has a stroke two weeks after starting a new blood pressure pill, but never had one before, that’s a red flag. This design removes personal factors like age or smoking habits that can muddy the waters in other studies.

Another approach is the case-control study. Researchers find people who had a bad reaction-say, a severe skin rash-and match them with people who didn’t. Then they look back to see who took the same drug. It’s like detective work, but with data. These methods are cheaper and faster than running new trials. A retrospective cohort study might cost $300,000. A new Phase III trial? Around $26 million.

But these tools aren’t perfect. They can miss over-the-counter drugs. They can’t always tell if someone actually took their medicine-or if they stopped because they felt sick. And even the best studies can’t fully rule out hidden factors. That’s why 15-30% of the links found in observational studies might be false alarms. That’s why findings from big database studies are always checked against other sources.

The Gold Standard and Its Limits

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) still hold the top spot for proving cause and effect. If a drug reduces heart attacks in a group randomly assigned to take it, versus a placebo group, that’s strong evidence. But RCTs are slow, expensive, and narrow. They often exclude older adults, pregnant women, or people with multiple chronic conditions-the very groups most likely to use the drug after approval.

So here’s the truth: RCTs tell us if a drug can work under ideal conditions. Observational studies tell us what happens when it’s used in the real world. The best safety science doesn’t pick one over the other. It uses both. The FDA requires RCTs for approval, but over 78% of its safety warnings since 2015 came from real-world data. That’s not a backup. That’s the core.

Where Things Go Wrong-And How We’re Fixing Them

Medication errors aren’t always about the drug. Sometimes, it’s the system. Nurses report near-miss errors weekly because EHR systems don’t talk to each other. Prescribers override 89% of drug interaction alerts in emergency rooms-not because they’re careless, but because the system floods them with too many warnings, most of which aren’t urgent. That’s alert fatigue. And it’s deadly.

At Kaiser Permanente Washington, they fixed one problem by creating a clear protocol for treating alcohol withdrawal with phenobarbital. Before, 15.3% of patients had severe withdrawal symptoms. After the protocol, that dropped to 8.9%. Simple. Evidence-based. Effective.

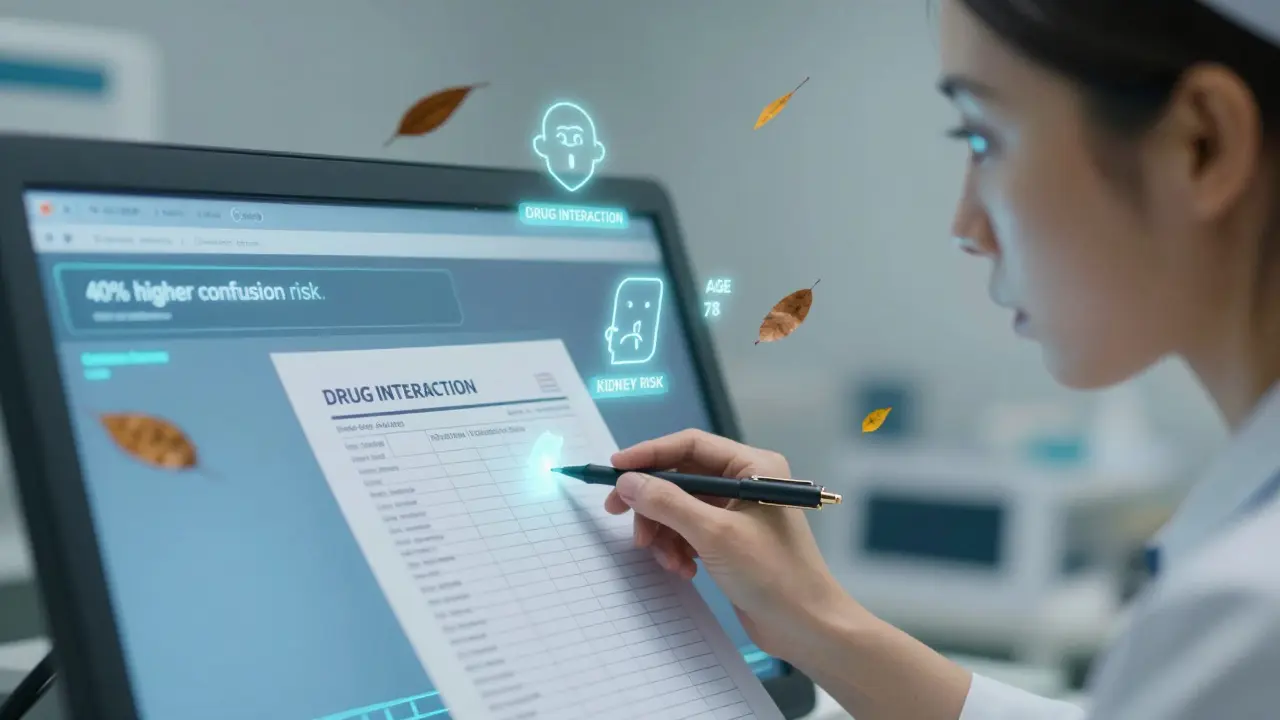

Other fixes are smarter tech. AI tools are now being tested to predict who’s at risk for a bad reaction before it happens. Early results show a 22-35% drop in high-alert medication errors. And new systems are starting to include medication decision intelligence-smart alerts that don’t just say “this drug interacts with that one,” but say, “this patient is 78-year-old with kidney disease and is on three other meds. This combination increases risk of confusion by 40%.” That’s not just a warning. That’s guidance.

Who’s Responsible for Safety?

It’s not just the FDA. It’s not just the drug company. It’s everyone. Pharmacists catch dosing errors. Nurses double-check labels. Doctors choose the safest option for a patient’s full health picture. Patients themselves need to know what they’re taking and why.

And the data backs this up. A 2023 study of 500 nurses in Iran found that medication safety competence explained 61% of safe care practices. The better trained and more confident the staff, the fewer errors. That’s not magic. That’s training. That’s culture.

But the system is uneven. Sixty-three percent of U.S. hospitals with more than 300 beds have a dedicated medication safety officer. Smaller clinics? Only 28%. That gap matters. A patient in a rural clinic might get the same drug as someone in a big city hospital-but without the same safety nets.

The Future: More Data, Smarter Systems

The next five years will change how we track drug safety. The FDA is preparing to use data from wearables-heart rate, sleep patterns, activity levels-to spot early signs of side effects. Imagine knowing someone’s heart is irregular before they even feel dizzy. That’s not sci-fi. It’s coming.

Also, more drugs are being approved with post-market safety studies already required. Nearly 4 in 10 new drugs now come with a mandatory safety study after launch. And the European Medicines Agency now requires a full risk management plan for every new medicine.

But challenges remain. Data privacy laws are shifting. A 2023 Supreme Court ruling weakened some protections for using health records in research. And compounded medications-those mixed in pharmacies, not mass-produced-are still largely unmonitored. The GAO flagged this as a serious gap.

Still, the direction is clear. We’re moving from reactive safety-waiting for harm to happen-to predictive safety-using data to stop it before it starts. The funding for this work is growing. The National Academy of Medicine predicts a 25% annual increase in research funding through 2030. Why? Because the population is aging. One in six Americans will be over 65 by then. And 35% of them take five or more medications daily. More drugs. More risks. More need for science.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a researcher to help make medication safety better. Keep a list of all your meds-prescription, over-the-counter, supplements. Bring it to every appointment. Ask: “What’s this for? What are the risks? What happens if I stop?”

If you’re a caregiver, watch for changes. A new confusion, a fall, a rash-these aren’t just “old age.” They could be a drug reaction. Speak up. If you’re a healthcare worker, push for better systems. Demand integrated tools. Push back on alert overload.

Medication safety isn’t a one-time check. It’s a continuous conversation-between patients and providers, between data and decisions, between science and real life. The evidence is out there. The tools are getting better. What’s missing is the attention. And that’s something everyone can change.

matthew martin

January 27, 2026 AT 21:10Man, I love how this breaks down the gap between clinical trials and real life. I work in primary care, and I see patients on meds that were never tested on folks with three chronic conditions and a side hustle. The data’s out there-we just gotta stop treating post-market surveillance like an afterthought.

jonathan soba

January 28, 2026 AT 03:31Let’s be real-most of these ‘real-world’ studies are garbage. Confounding variables everywhere, people not even taking their pills, and then they act like it’s gospel. If you can’t randomize it, it’s just noise dressed up in fancy stats.

Kevin Kennett

January 28, 2026 AT 13:09Jonathan, you’re missing the point. Just because it’s messy doesn’t mean it’s useless. Real people aren’t lab rats. We’re talking about grandmas on six meds, teens on antidepressants, pregnant women who got prescribed something off-label-these are the people the trials ignored. The data’s noisy, sure, but it’s the only data we’ve got for them.

Katie Mccreary

January 30, 2026 AT 11:54Also, why do we let drug companies control the data? They hide negative results all the time. And don’t even get me started on how they pay for ‘independent’ post-market studies.

doug b

February 1, 2026 AT 01:18Alert fatigue is real. I’ve seen nurses ignore warnings because the system screams ‘DANGER’ for every little interaction. One time, a patient got a drug that interacted with a supplement they’d stopped taking 3 months ago. The system didn’t know. Neither did the doctor. We need smarter alerts, not louder ones.

Rose Palmer

February 1, 2026 AT 19:15While I appreciate the emphasis on observational data, it is imperative to underscore that randomized controlled trials remain the methodological gold standard for establishing causal inference. To subordinate them to retrospective analyses risks the erosion of evidentiary rigor in clinical pharmacology.

Howard Esakov

February 2, 2026 AT 12:29Wow. So we’re just gonna trust random hospital data from people who can’t even spell ‘pharmacokinetics’? 😒 I mean, I get it-big pharma’s evil, but this is just data-worship without the math. I’m 98% sure half these ‘signals’ are just correlation with a side of confirmation bias. 🤷♂️

Jess Bevis

February 2, 2026 AT 21:38My cousin in rural Texas got prescribed a new blood thinner. No safety officer. No EHR integration. Just a scrip and a prayer. This isn’t science-it’s geography.

John Rose

February 2, 2026 AT 22:36One thing this post doesn’t mention: patient-reported outcomes. Apps like MyTherapy or PatientsLikeMe are collecting real-time data on side effects-way before hospitals even notice. That’s the future. Real-time, patient-driven safety nets.

Lance Long

February 3, 2026 AT 09:53Let me tell you about my aunt. Took a new statin. Started forgetting her own birthday. Went to the doctor-‘Oh, it’s just aging.’ Three months later, she was in rehab. That drug was pulled from the market in Europe a year before. But here? Nobody knew. Nobody cared. This isn’t science. It’s a waiting game. And we’re all just pawns.

SRI GUNTORO

February 4, 2026 AT 14:52People just don’t take responsibility anymore. If you’re on five pills, it’s your fault. You didn’t read the leaflet. You didn’t pray enough. Stop blaming the system. God gives us wisdom to choose wisely.

Timothy Davis

February 5, 2026 AT 10:51SCCS? Please. That method assumes temporal stability of confounders-which is laughable in polypharmacy patients. And you cited Kaiser’s data like it’s peer-reviewed gospel? Their data is proprietary, unreplicated, and filtered through corporate analytics teams. I’ve reviewed their methodology. It’s a statistical house of cards.

Jeffrey Carroll

February 5, 2026 AT 13:56Just one thing: if you’re on more than three meds, ask your pharmacist for a med sync. It’s free. They’ll sort your pills, catch interactions, and actually call your doctor if something looks off. Most people don’t know this exists. Small fix. Huge difference.