The U.S. generic drug market didn’t just happen. Before 1984, if you needed a cheaper version of a brand-name medicine, you were out of luck. The system was stacked against copycat drugs. Generic manufacturers had to run full clinical trials-just like the original drugmaker-to prove their version was safe and effective. Even if the chemical formula was identical, the FDA didn’t accept that. It was expensive. It was slow. And it meant most people paid full price for medications they couldn’t afford.

What the Hatch-Waxman Amendments Actually Did

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act-better known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments. It was a deal. A complicated, carefully negotiated deal between two powerful sides: big pharmaceutical companies that wanted to protect their patents, and smaller drugmakers who wanted to bring affordable copies to market.

The law had two main goals. First, make it faster and cheaper to approve generic drugs. Second, give brand-name companies extra patent time to make up for the years they lost waiting for FDA approval. That’s the core of the compromise.

Before Hatch-Waxman, a generic company couldn’t even start testing a copy of a patented drug until the patent expired. A 1984 court case, Roche v. Bolar, made it clear: doing any testing before patent expiry was illegal. That meant patients waited longer for cheaper options-even if the drug was about to lose patent protection.

Hatch-Waxman changed that. It created a legal safe harbor. Now, generic companies could start testing their versions while the original patent was still active. As long as they were doing it for FDA approval-not for sale-they weren’t breaking the law. That single change cut years off the timeline to market.

The ANDA: The Engine Behind Generic Drug Approval

The real game-changer was the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. Before Hatch-Waxman, every new drug needed a full New Drug Application (NDA)-thousands of pages of clinical data. For generics, that was nonsense. If the brand-name drug had already been proven safe and effective, why make generic makers repeat every single study?

The ANDA process said: ‘You don’t need to prove safety or efficacy again. Just prove your version works the same way in the body.’ That’s called bioequivalence. It means your pill releases the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name version. No more repeating animal studies or Phase III trials. Just a few small human studies. That cut development costs by 80-90%.

By 2023, nearly 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generic drugs. That’s up from less than 19% in 1983. And those generics cost, on average, 80-85% less than the brand-name version. That’s not a coincidence. That’s Hatch-Waxman working as designed.

Patent Linkage and the Orange Book

To keep things fair, Hatch-Waxman created a system to track which patents protected which drugs. The FDA publishes the Orange Book, a public list of all approved drugs and the patents tied to them. Brand-name companies must list every patent they think applies to their drug.

When a generic company files an ANDA, they have to say how they’re dealing with those patents. There are four options, but one is the most powerful: Paragraph IV certification. This is where a generic company says, ‘Your patent is invalid, or we’re not infringing it.’

That’s a legal challenge. And if you’re the first to file a Paragraph IV certification, you get a huge reward: 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s a massive financial incentive. It’s why companies race to be first.

But here’s the catch: the brand-name company can sue you for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA can’t approve your drug for 30 months-unless the court rules in your favor sooner. This 30-month stay is a double-edged sword. It gives brand-name companies time to defend their patents. But it also lets them delay competition, even if their patent is weak.

The Flip Side: Pay-for-Delay and Evergreening

Hatch-Waxman was meant to balance innovation and access. But over time, loopholes emerged. One of the biggest is pay-for-delay. That’s when a brand-name company pays a generic maker to stay out of the market. Instead of fighting in court, they cut a deal: ‘We’ll give you millions, and you won’t launch your cheaper version.’

The Federal Trade Commission found 668 of these deals between 1999 and 2012. They estimate these agreements cost consumers $35 billion a year in higher drug prices. The FTC has tried to stop them. Courts have cracked down. But they still happen.

Another tactic is evergreening. That’s when a drugmaker makes a tiny change-like a new pill shape or a slightly different dosage-and files a new patent. Suddenly, the original patent is about to expire, but now there’s another one. And another. And another. This keeps generics out for years longer than intended.

Some companies also file ‘citizen petitions’ with the FDA-often with no scientific basis-just to delay approval. These petitions tie up the agency’s resources and buy time for the brand-name drug to keep raking in profits.

How the System Has Evolved Since 1984

Hatch-Waxman wasn’t the end of the story. It’s been updated. In 2012, Congress passed the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). This let the FDA charge fees to generic manufacturers to fund faster reviews. Before GDUFA, it took an average of 30 months to approve an ANDA. By 2022, that dropped to under 12 months.

The FDA also cracked down on the 180-day exclusivity loophole. In 2003, they announced that if two companies file a Paragraph IV certification on the same day, they share the 180-day exclusivity. That stopped companies from gaming the system by filing at the exact second the clock started.

And in 2023, Congress introduced the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which aims to make pay-for-delay deals harder to hide. It gives the FTC more power to investigate and block them.

Who Benefits? Who Doesn’t?

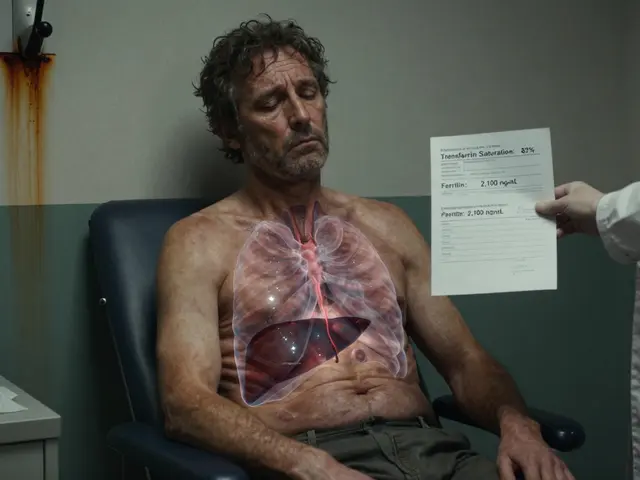

Patients benefit the most. Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $370 billion every year. That’s money that goes to hospitals, insurance, and out-of-pocket costs. A diabetic patient on insulin might pay $25 for a generic instead of $300 for the brand. That’s life-changing.

But brand-name companies argue they need strong patent protection to justify the $2.6 billion it takes, on average, to develop a new drug. Without Hatch-Waxman’s patent term extension, they say innovation would slow. And there’s truth to that. The law gave them up to five extra years of market exclusivity to make up for the time lost during FDA review.

The problem? Some companies use that extension to extend monopolies far beyond what Congress intended. A drug that should have faced competition in 2015 might still be protected in 2025 because of layered patents and regulatory tricks.

And while the 180-day exclusivity was meant to reward the first challenger, it’s become a tool for strategic delay. Some companies file Paragraph IV certifications just to block others, then sit on the approval without launching the drug. The market stays closed. Prices stay high.

Is Hatch-Waxman Still Working?

Yes-and no.

It created the modern generic drug industry. It made affordable medicine a reality for millions. It’s responsible for the fact that today, you can walk into any pharmacy and get a generic version of almost any prescription drug.

But the system is strained. The original balance has tilted. Brand-name companies have become better at gaming the rules. The 30-month stay is often used as a delay tactic. The 180-day exclusivity is sometimes held hostage. And pay-for-delay deals still slip through.

The FDA and FTC are trying to fix it. But real change needs Congress. Until lawmakers update Hatch-Waxman to close these loopholes, the system will keep favoring profits over patients.

For now, Hatch-Waxman remains the foundation. It’s not perfect. But without it, the U.S. would still be paying $300 for insulin. And millions wouldn’t be able to afford their meds at all.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act, formally called the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, is a U.S. law that created the modern system for approving generic drugs. It lets generic companies use the FDA’s prior safety data to prove their versions work, as long as they show bioequivalence. It also gives brand-name drugmakers extra patent time to make up for delays in FDA approval.

How did generic drugs get approved before Hatch-Waxman?

Before 1984, generic manufacturers had to submit full New Drug Applications (NDAs), including their own clinical trials proving safety and effectiveness-even if their drug was chemically identical to the brand-name version. This made the process too expensive and slow, and only a small fraction of drugs had generic versions.

What is an ANDA?

ANDA stands for Abbreviated New Drug Application. It’s the streamlined approval process created by Hatch-Waxman for generic drugs. Instead of running full clinical trials, generic makers only need to prove their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug-meaning it delivers the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same rate.

What is Paragraph IV certification?

Paragraph IV certification is when a generic drug company tells the FDA that a brand-name drug’s patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed by their product. It’s a legal challenge. The first company to file a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic, which is a huge financial incentive.

Why do some generic drugs take so long to come out after a patent expires?

There are several reasons. Brand-name companies may file lawsuits triggering a 30-month FDA approval delay. Some generic companies file Paragraph IV certifications just to block competitors without launching their product. Pay-for-delay deals also keep generics off the market. And some drugmakers use ‘evergreening’-filing new patents on minor changes-to extend exclusivity.

How much cheaper are generic drugs?

Generic drugs cost, on average, 80-85% less than their brand-name equivalents. In 2023, they accounted for about 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., saving the healthcare system roughly $370 billion annually.

Is the Hatch-Waxman Act still relevant today?

Yes. It’s the legal foundation for nearly all generic drug approvals in the U.S. But many experts say it needs updating. Loopholes like pay-for-delay, evergreening, and strategic use of the 30-month stay have undermined its original intent. New laws are being proposed to fix these issues, but the core framework still holds.

Webster Bull

December 12, 2025 AT 01:22Hatch-Waxman was the moment generic drugs stopped being a pipe dream and became a lifeline. No more waiting 10 years to get a $5 insulin pill. That’s real change.

Bruno Janssen

December 12, 2025 AT 17:38i just read this and felt nothing. like, i get it, but also… why does this matter to me? i just take my pills.

Tommy Watson

December 13, 2025 AT 05:46so let me get this straight… big pharma pays generics to NOT sell cheaper drugs?? and we’re supposed to be SURPRISED that prices are still insane?? this isnt a law, its a joke with a law book cover. #payfordelay #ripmywallet

Karen Mccullouch

December 13, 2025 AT 09:49AMERICA BUILT THIS SYSTEM. WE MADE GENERIC DRUGS POSSIBLE. OTHER COUNTRIES STILL PAY 5X. STOP WHINING. IF YOU CAN’T AFFORD MEDS, GET A JOB. #AMERICAFIRST #HATCHWAXMANWORKS

sharon soila

December 14, 2025 AT 23:25This law changed lives. Not just because of cost, but because it restored dignity. No one should have to choose between feeding their child and filling a prescription. The system isn’t perfect, but without this, millions would still be suffering in silence. Thank you, Congress - even if it took 40 years to get here.

nina nakamura

December 16, 2025 AT 00:0990% of prescriptions are generic? That’s not Hatch-Waxman working. That’s the system being gamed. Most generics are made in India and China. The real issue is supply chain control not approval pathways. Also the 180-day exclusivity is a cartel. And the FDA approves 95% of ANDAs without a single inspection. Wake up.

Cole Newman

December 17, 2025 AT 19:25yo did u know that some companies file paragraph iv just to block others and never even launch? like they pay lawyers to sit on it for 5 years. that’s not innovation, that’s corporate sabotage. and the fda lets it happen. smh.

Casey Mellish

December 19, 2025 AT 12:43As an Australian, I’ve seen how our system works - no patent evergreening, no pay-for-delay, and generics hit the market within weeks of expiry. The U.S. system isn’t broken because of Hatch-Waxman - it’s broken because of greed. The law was brilliant. The loopholes? That’s on lobbyists. Fix the rules, not the framework.

Tyrone Marshall

December 20, 2025 AT 16:35Let’s not forget who this law was really for: the grandma on insulin, the veteran on blood pressure meds, the single mom buying antibiotics for her kid. Hatch-Waxman didn’t just change the market - it changed the moral compass of American healthcare. Yes, there are abuses. But the solution isn’t to tear it down. It’s to strengthen it - with transparency, with enforcement, and with courage. We can do better. We have to.